SHOWNOTES

Great Western Air Ambulance Charity

Stoic Books

The Tao of Seneca - Tim Ferris

The Daily Stoic - Ryan Holiday

Running Books

Born To Run - Christopher McDougall

Ultramarathon Man - Dean Karnazes

Running & Exercise

AI

I used an AI clone of my voice via Speechify to narrate the post below. It is uncanny how accurate it is. The other segments were all me.

Blackness. An unnatural and absolute absence of everything. A blackness so intense that it couldn’t possibly exist in real life. That was my impression of it. An anti-experience. A heavy, massive and, utter void in my life's timeline.

Since the tender age of 26, when Mike O'Reirdan (the “grandfather"of my career) offered me my first leadership role, I have never shied away from challenges. I have a tatty fortune cookie aphorism which tells me “Don’t ignore your needs in the area of new challenges”. I took this to heart when I found it, and still do.

Subscribe to Push To Start for free to receive new posts and support my work.

On the theme of challenges, I got into ultra-running about 15 years ago, just as it was becoming popular, partly due to the books Ultramarathon Man and Born To Run. I much preferred the long-haul events, and the necessary mind control needed to complete such distances. To me ultras are journeys, not just races. The views, the struggles, the ups and down (literal and psychological) and the resultant insights are what make them worth the effort.

To date, I have 18 ultra finishes to my name, and one DNF at 62 miles of 100. One of my very few regrets in life is that I bailed on that event, the last ever Caesar’s Camp.

So imagine my horror, when, on the afternoon of the 30th August 2023, at the age of 54, I began to wake up in the ICU at the local general hospital, with absolutely no knowledge of how I got there.

My emergence from the aforementioned blackness, was patchy, flickering like a life exposed by lightning. A fragmented, sedative addled, and somewhat horrifying experience; at least until my senses and awareness had fully rebooted.

My wife, Claire, was clutching my hand, anxiety pulsing across her face, her eyes searching for the me she knew, hoping not to see someone damaged or distinctly altered.

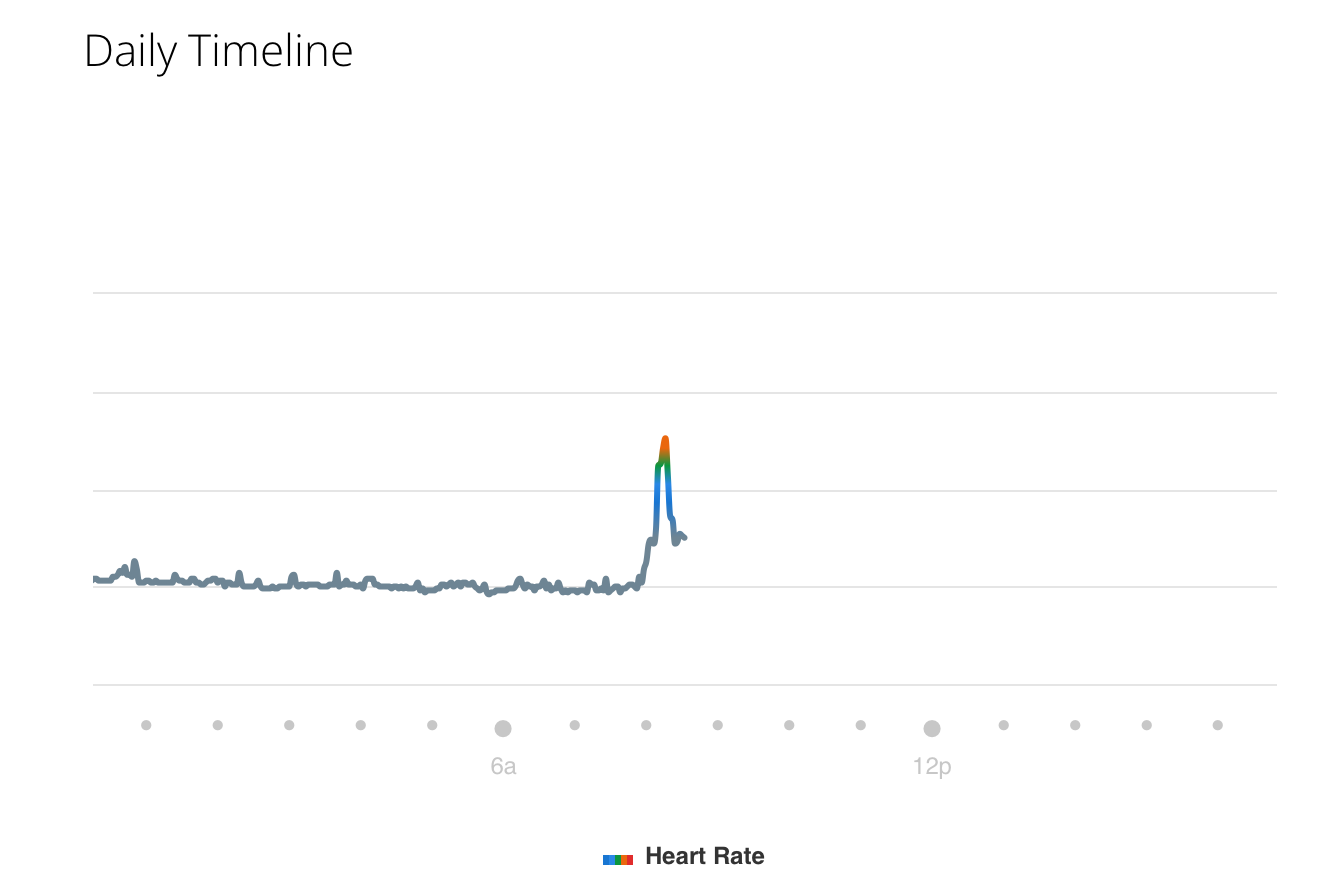

On the prior Saturday (the 26th of August), I had run a slightly troubled ten mile training run with my friend, Mark. By troubled, I mean that I was at the apex of a training block, ahead of running the 102 miles event, the Cotswold Way Century. Mark and I were due to run it two weeks later. I was probably as fit as I had ever been, but could feel the approach of overtraining on my recovery and my performance. I went to bed that night expecting my taper to begin and some well earned rest in the days ahead.

I’d suffered a heart attack, and consequential cardiac arrest. It happened whilst I was asleep, on the morning of the twenty seventh of August. This, occurring as it had, should have killed me; which technically, it had for a short while.

Thanks to the alertness and the expert CPR efforts of my wife, Claire, coupled with the rapid response of the South West Ambulance Service, I was resuscitated and stabilised after a couple of defibrillator shocks. The Great Western Air Ambulance arrived shortly afterwards, and their advanced paramedic put into a protective coma before I was loaded onto an ambulance for onward processing.

The home security camera footage of me being wheeled across my drive and into an ambulance, is the most surreal thing I have ever seen.

The news of what had happened struck me hard. Bizarrely, one of my first cogent thoughts was “Will I be able to run?”. With that thought came the realisation that my identity as a runner was a lot stronger than I had realised, especially now there was a probability I might not be able to again. There and then, I resolved to find out.

But first, I had to overcome the here and now. In those first few days, I was haunted by a three day long blackness in my life’s timeline, a disabling amount of pain and unusual frailty, and an unexpected road to recovery I most definitely wasn’t prepared for.

Being in hospital, with strict visiting hours, I was alone with my thoughts a lot of the time. My mind was struggling to make sense of what and why it had happened. I had a niggling suspicion that I had left my fitness drive too late in life, was a rumination that tries hard to take hold. Having spent a lot of time in recent years meditating, I have become quite adept at noticing unwanted thoughts and used this skill to defer the conversation, and instead, get up and drag my drip and mobile ECG for a stroll around the corridors. My mind was working well, enabling me to fix my focus on not allowing this event to dictate the onward path of my life. Despite the fear, the upset, and the shock of what had happened, I had a good life and I decided that this was not going to get the better of me.

Despite having been lured into the Stoics and their teachings by Tim Ferris and Ryan Holiday years before, in the face of the facts, I was slightly surprised by the stoicism I was actually able to muster. I suppose I had prepared myself for my “challenge of all challenges”; to have met this obstacle - and realising that there was no going around it - the obstacle, really was, the way.

During my ten day stay in hospital, I had three stents fitted. Two on arrival, to my left anterior descending artery, delightfully known as the widow-maker, and another, the day before discharge, to my right coronary artery. Both arteries had been almost completely blocked. Interestingly my right artery had created three collaterals (tiny extra vessels) to bypass the blockage. As soon as I could, within the first week, I began going outside and walking. Having trained to run 100 miles, I had a strong drive to move, to cover ground, to breathe, despite my traumatised ribcage, to remind my body I was alive and able.

By mid October I was walking 45 miles a week. Then, in November, I was cleared to exercise after an ultrasound of my heart showed it had recovered to substantially normal function. Not unscathed, but pretty much.

I was medically cleared to exercise and on Claire’s suggestion, we began the NHS Couch 2 5K programme. This made sense, to allow me to feel my way back toward effort and just take it slowly. We did this whilst I completed the excellent Cardiac Rehab provided by Gloucestershire NHS. On the last official Cheltenham parkrun of 2023, Claire and I completed the programme. A small but significant win. I was ready.

I went on to train until March, for my first half marathon since my “event”; an ecstatic 2 hours and 49 annoying seconds, giving me more confidence to continue training.

In May, I completed the Marlborough Downs Challenge, a favourite 33 mile run with a handy bail out point at 12 miles. I didn't need it, and managed to come in approximately 12 minutes faster than my previous running a few years earlier.

Next was the Chilterns Ultra in July (another 50k) with Mark, which was great, despite a significantly hard last five miles, due more to a lack of training and some trepidation than anything cardiac.

I paced my friend Adam around the Forest of Dean Autumn Half in October, and finished my year with Mark again, leading me around the Broadway Marathon, another hilly jaunt, where I had acquired slightly more pace and consistent stamina. Finally, I was back.

I am profoundly grateful for the existence of a worldwide group called Cardiac Athletes. A group of thousands, who have stepped over their individual heart problems to strive towards goals that most cardiacnormal people would struggle to meet. This is my new tribe, and I’m privileged to have a fellow member, Forrest, in my home town, who has been a valuable source of knowing conversation and guidance for me.

Having achieved these things (and many others) since my cardiac arrest, I am utterly delighted to still be here, with a heightened awareness of the benefits of being alive. I have a newfound preference to care less about things now, and a fiery hatred of wasting my time. Being able to run, swim and relish the world I still live in, and the lives of those I share it with, is a daily source of joy.

I am beyond grateful to my wife, family and friends who have allowed me to re-find my feet, my way. Similarly for the flawless service from the NHS Gloucestershire paramedics, cardiology geniuses, nursing team, cardiac rehab and GP teams.

There is life after death, and it is good.

Footnote

It bears mentioning that the unimpaired survival rate for someone that suffers an Out Of Hospital Cardiac Arrest in the UK is vanishingly small. Although variations in survival rates occur regionally, the number quoted in nationwide statistics (2022) is less than 8% of people survive an initial 30 day period.

This paltry survival rate mostly applies to those of us that were lucky enough to get early CPR and defibrillation.

So, if there is one take away for the readers of my story, it is to learn CPR. Become aware of the chain of survival, and how to prevent people needlessly dying. Dying because bystanders are not able, confident enough, or sure how, to get involved and help. Every minute spent in cardiac arrest without intervention, reduces chances of survival by 10%. CPR and defibrillation are essential to keep their brains alive until the professionals arrive.

Are you a cardiac arrest survivor?

If you are, and are interested in sharing your survival story, please get in touch for an informal chat about what’s involved.

Disclaimer

The content provided in this episode, on the Push To Start website, or through any linked resources, is for informational purposes only and is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your GP, cardiologist, or another qualified healthcare professional with any questions you may have regarding your health or a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay seeking it because of something you have heard or read here.

Share this post